Why stop now? Let’s find out how, and to what extent, the rules against indiscriminate spying are enforced. We’ve learned a lot from the dialectic of unauthorized and authorized disclosures. That’s to Snowden’s credit: Without his leaks, the government wouldn’t have shown us anything. This week it declassified the most explicit such document: an order issued in April by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court. The government, in turn, has released documents indicating that the NSA is more constrained than Snowden originally implied. It’s impossible for him to do what he was saying he could do.” The screenshots leave Rogers with a lot to explain. Mike Rogers, the Republican chairman of the House Intelligence Committee, has scoffed that Snowden “was lying” when he claimed the ability to “read everybody’s emails.” Rogers said Snowden had misrepresented what “the technology of the programs would allow one to do. But the overarching story lines - Snowden’s disclosures about what the NSA can do, and the government’s disclosures about what the NSA may do - are useful for checking and clarifying one another.

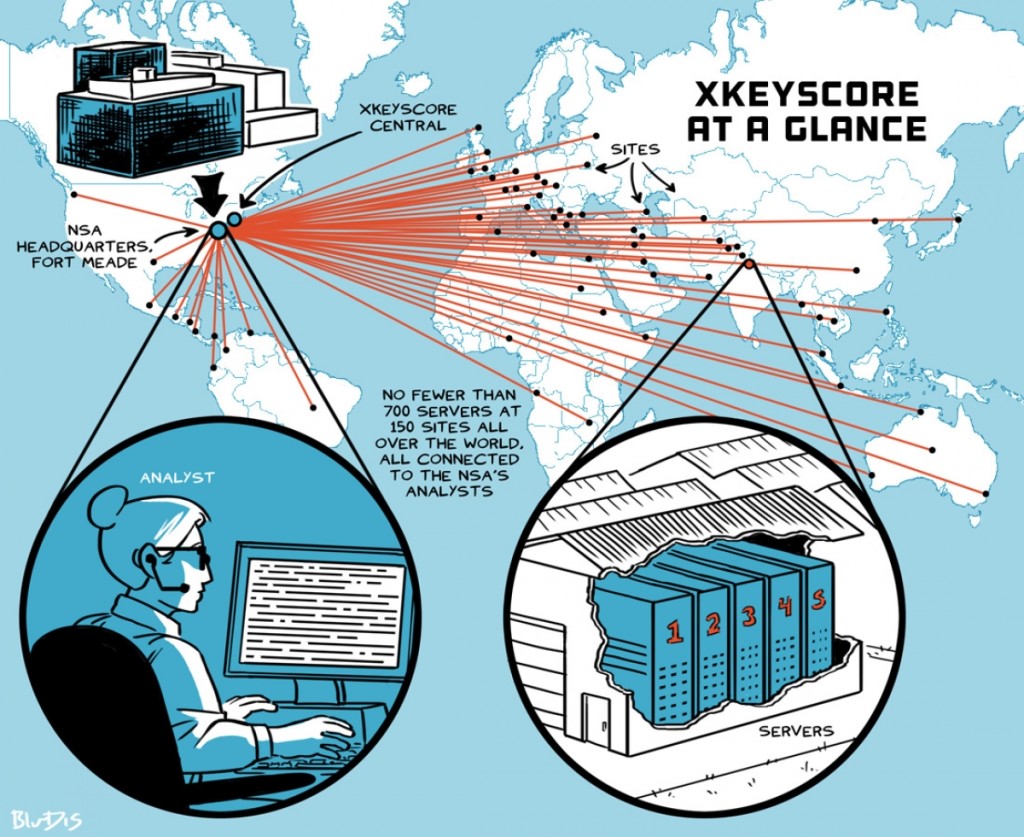

In this week’s exchange, the government and the Guardian were talking about two different programs: one for domestic phone metadata, the other for foreign Internet content. The word prior hints that the agency does have procedures to monitor and punish abuse. The Guardian also reports that XKeyscore “allows analysts to search with no prior authorization” through NSA databases. That’s a legal assertion unsubstantiated by the screenshots. His precise claim was that “I, sitting at my desk, certainly had the authorities” (emphasis added) to wiretap anyone. The Guardian says its report vindicates Snowden’s claim that “I, sitting at my desk,” could “wiretap anyone, from you or your accountant, to a federal judge or even the president.” That’s not quite what Snowden said. He reported that a previously undisclosed NSA tool, known as XKeyscore, “allows analysts to monitor a virtually unlimited array” of Internet activity and to search “vast databases containing emails, online chats and the browsing histories of millions of individuals.” To prove it, the Guardian published slides from an NSA training document - apparently, screenshots of the search forms in which an analyst would input an email address, Facebook user name, or other surveillance target.īut the Guardian, like the government, isn’t telling the whole story. Meanwhile, in the Guardian, Greenwald was telling his side of the story.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)